1. The Genesis of Urgency – A Project Born of Fear

In 1939, as the world tilted toward war, a letter from Albert Einstein to President Roosevelt changed everything. It warned that Nazi Germany might be developing a weapon of unprecedented power — one based on the principles of nuclear fission.

Within three years, that warning evolved into The Manhattan Project, a U.S.-led initiative involving the United Kingdom and Canada, to create an atomic bomb before the Axis powers could.

But here’s what made it unique from a project management perspective: there was no precedent, no roadmap, and no clarity. The project began with uncertainty as its foundation — and had to integrate dozens of scientific unknowns into a single functional outcome.

Lesson: Integration management begins when clarity doesn’t exist — not after it arrives.

2. The Architecture of Secrecy – Designing Integration Without Visibility

Most modern project managers think of integration as communication.

But the Manhattan Project was built on compartmentalization — the deliberate isolation of teams to maintain secrecy.

a) The Paradox of Compartmentalized Integration

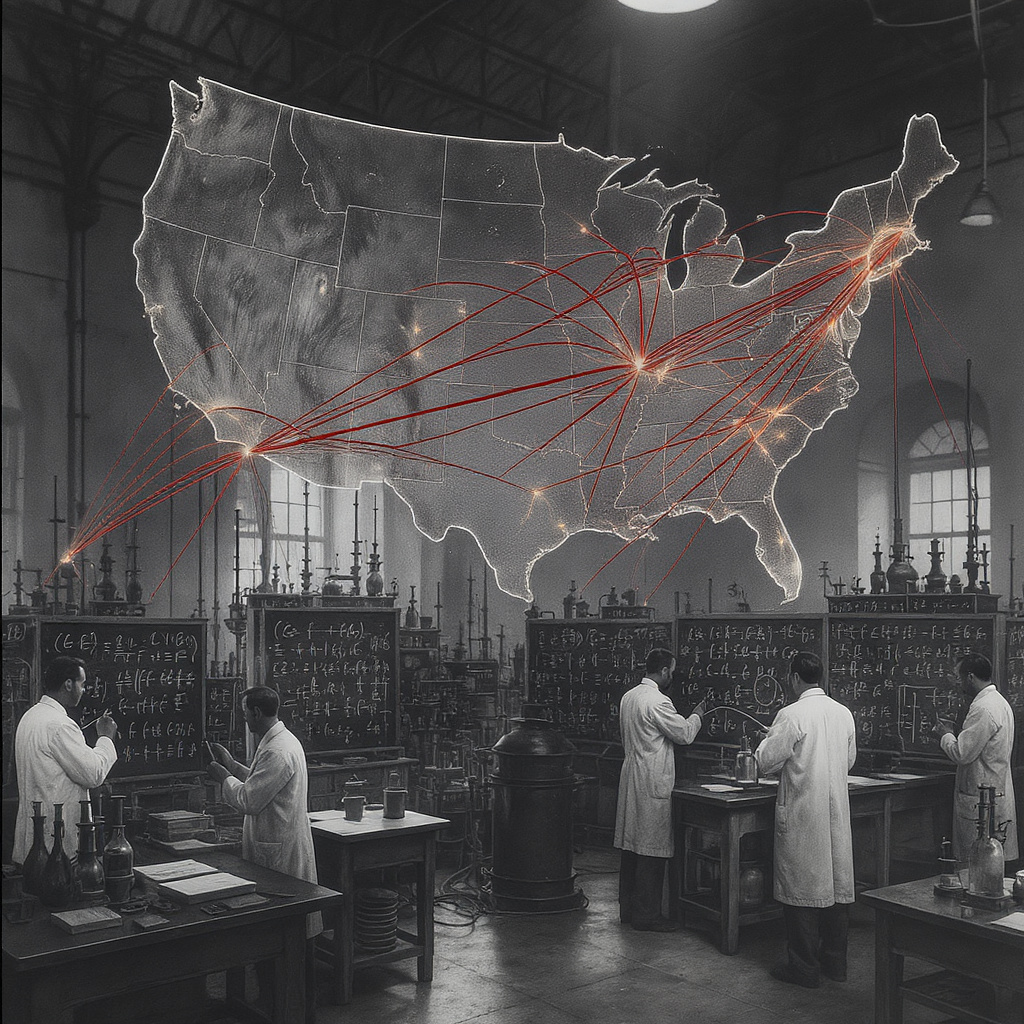

- Each research team worked in isolation, unaware of the larger goal.

- Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Hanford were separated by thousands of miles and purposefully siloed.

- And yet, through controlled information channels and centralized decision-making, their outputs aligned perfectly.

How? Because Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves designed an integration hierarchy rather than an information network.

Each function — physics, engineering, logistics, and military — was independently empowered but strategically aligned through shared milestones and a unified end goal.

Lesson: True integration isn’t about everyone knowing everything; it’s about everyone knowing enough to move forward.

3. Leadership Integration – When Scientists Met Soldiers

Perhaps the most delicate balancing act was between scientific curiosity and military discipline.

The project had two distinct cultures:

- The scientists, led by Oppenheimer, driven by discovery and debate.

- The military, led by Groves, focused on deadlines, deliverables, and control.

Most projects fail when these worlds collide. The Manhattan Project thrived because they didn’t try to merge them — they interlocked them.

- Groves provided structure, authority, and funding.

- Oppenheimer provided vision, creativity, and intellectual integration.

Together, they formed one of history’s most unlikely yet effective leadership pairs.

Lesson: Integration is not about harmony — it’s about harnessing productive friction.

4. Systems Thinking Before Systems Existed

Long before “systems engineering” became formalized, the Manhattan Project embodied it. Every subsystem — uranium enrichment, plutonium production, weapon design, and testing — had to function independently but converge at a single point in time: the Trinity Test.

a) Synchronization Without Software

With no digital dashboards or cloud databases, integration relied on discipline and physical reporting systems.

- Weekly summaries traveled through couriers.

- Critical data was coded and cross-validated manually.

- Every test had to be traceable, logged, and approved before the next stage.

Despite the analog environment, feedback loops were short and relentless.

Lesson: Integration thrives not on technology, but on accountability and cadence.

5. Ethics, Ego, and the Cost of Convergence

The greatest integration challenge wasn’t technical — it was moral.

Scientists like Oppenheimer and Fermi knew the implications of their work. As success neared, doubts emerged. Yet, project governance had no framework for ethical integration — how to merge human conscience with mission execution.

This missing link still haunts modern project management. AI, genetic engineering, and autonomous weapons face the same dilemma — how do you integrate ethics into objectives?

Lesson: Integration without ethical boundaries is efficiency without wisdom.

6. Post-War Legacy – The Blueprint of Modern Integration Management

The Manhattan Project ended in 1946, but its methods birthed entire disciplines that define project management today:

- Program Integration Offices (PIOs): Modeled after the project’s centralized coordination system.

- Work Breakdown Structures: Rooted in the task decomposition used at Los Alamos.

- Configuration Management: Emerged from the strict documentation control used in nuclear testing.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: A direct descendant of scientific-military teamwork.

Even NASA’s Apollo Program was inspired by the Manhattan Project’s integration philosophy — distributed expertise, unified purpose.

Lesson: The tools may evolve, but the architecture of integration remains timeless.

7. Integration in Modern Complex Projects – From Atoms to Algorithms

In today’s era of AI systems, digital transformation, and space exploration, integration challenges resemble those faced in the 1940s:

- Diverse teams.

- Conflicting goals.

- High uncertainty.

- Massive stakes.

Project Integration Management today demands:

- Unified vision even in distributed teams.

- Iterative alignment through agile methods.

- Decision transparency even in hierarchical setups.

- Ethical governance as part of integration frameworks.

The tools are faster, but the mindset must remain deliberate.

Lesson: Integration is not about combining — it’s about cohering.

8. Final Reflection – The Invisible Thread That Holds It All Together

When the first atomic test lit up the desert sky, it wasn’t just the birth of a weapon — it was the birth of a new way of thinking about projects.

The Manhattan Project showed that integration is the invisible thread between chaos and creation. It demands alignment of not just systems and schedules, but of people, purpose, and power.

Every modern project — whether it’s building a digital platform, a spacecraft, or a renewable energy grid — faces its own version of the same question:

Can we integrate ambition without losing our humanity?

The Manhattan Project answered yes — but at a cost that still echoes across generations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.